Bruges blossoms

In the 14th and 15th centuries, Bruges was the most important trading centre in northern Europe and one of the largest cities north of the Alps. The advance of technology, trade, and ingenuity brings wealth, but also exploitation, poverty, and misery.

During the 13th century, the population of Ieper grew to 40,000, Bruges to around 50,000, and Ghent to 80,000. Flemish cloth centres flourish. The Flemish cloth is a luxurious fabric made of wool. Anyone looking at a medieval painting with notable figures anywhere in Europe has a good chance to see that at least one of those figures is wearing Flemish cloth. “Let’s show off that wealth,” was a common thought among many Bruges residents.

Bruges flourished and became a merchant’s paradise. Thanks to a covered Waterhalle (1294-1787) on the Markt, loading, unloading, and trading could continue even in inclement weather. The list of Bruges’s trades is long: bakers, butchers, blacksmiths, cobblers, tailors, fullers, tanners, stonemasons, soap makers, apothecaries, candle makers, painters, weavers and, of course, brewers of beer and mead. And Bruges’s merchandise is also diverse: exotic dates, figs, African spices, cumin, marzipan, saffron, pomegranates, lemons, Italian cheeses, perfumes…

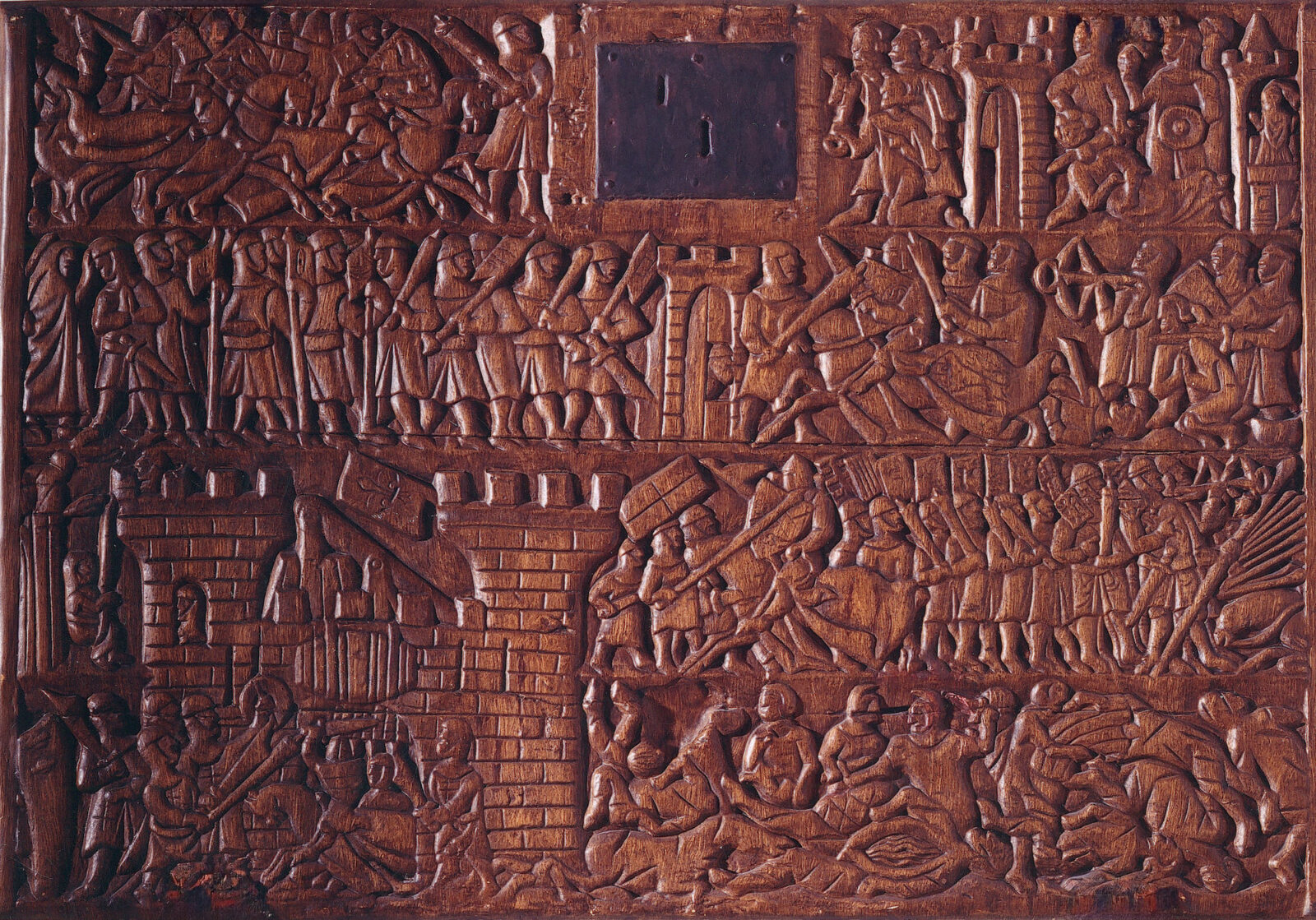

Bruges’s towering growth is also reflected in the Belfry. The third octagonal section of the tower was raised to some 27.4 metres high between 1482 and 1486. This is equipped with belfry windows to broadcast the sound of the carillon over the city. The city’s most important documents are kept in the Belfry. There are two large chests with ten different locks: nine are for the zwaardekens, trade delegates; the tenth is for the count’s representative. All must be present to open the chest.